Success Story

AI-powered precision imaging of the cervical spine

Precision Imaging

Neck and back pain is a major public health problem. Many people suffer from chronic pain, which can severely impact their daily lives and ability to work. The PHRT-funded project “AI-powered precision imaging of the cervical spine”, a collaboration between EPFL, ETH Zurich, and Balgrist University Hospital, aimed to develop advanced MRI technologies to improve the assessment of the cervical spine, particularly the neck region.

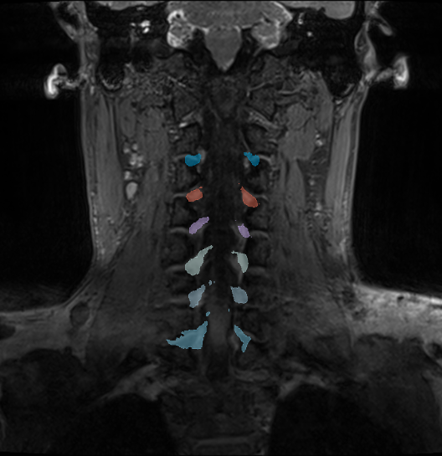

Specifically, the idea was to develop a new MRI acquisition technique that would allow the individual nerve roots emerging from the spine to be visualized. The spinal cord is the main conduit for nerves that branch out and connect to different parts of the body. When one of these nerve roots becomes compressed, it can cause pain that radiates through the arms, legs, or other areas. By enabling precise identification and visualization of these nerve roots, the project aimed to detect and analyse such compressions and their effects.

Current high-resolution MR imaging techniques are quite slow. The process takes about one hour and requires the subject to remain perfectly still in the scanner. This can be challenging even for healthy individuals, and even more so for patients experiencing pain. Therefore, reducing the scan time was a key objective of the project. As part of this collaboration, Reto Sutter (Balgrist University Hospital, University of Zurich) played a key role in optimizing the MRI acquisition protocols, both at 3T and 7T field strength, enabling high-resolution visualization of the cervical spinal cord and nerve rootlets. The Balgrist team contributed substantially to refining the cervical spine sequences to ensure robust image quality across both high-field MRI (7T) and clinical MRI (3T) systems. Their work established the technical foundation for the subsequent AI-based reconstruction efforts.

Left: Coronal cross-section of an MRI showing the cervical area. Colored regions are predicted nerve roots. Right: A 3D reconstruction of the nerve roots in the area to help identify compression.

Optimizing the process with machine learning

The group led by Ender Konukoglu focused on accelerating the acquisition process using AI techniques. The central question was whether it would be possible to reduce the scan time from one hour to 10-15 minutes while maintaining the same image quality. Achieving this would make the procedure more accessible to patients. To accomplish this, the scientists trained a machine-learning model using pairs of fast and slow acquisitions. This model would then learn to predict or reconstruct the missing information in the fast scans based on the high-quality reference data it had seen – essentially filling in the details intelligently. The EPFL team, headed by Jean-Philippe Thiran and his postdoc – now a professor in Paris – led this effort. They are currently finalizing their results and preparing them for submission to a scientific journal.

Another goal was to extract quantitative measurements from the scans. Specifically, the diameter of each nerve root needed to be measured automatically and the degree of compression determined. This information can help clinicians in planning treatment options. It is difficult to assess such details merely by looking at MRI images. “Thanks to the collaboration with Balgrist University Hospital, we were able to acquire a dataset of 40 healthy individuals for these measurements”, says Konukoglu. The publication will make this dataset publicly available, providing a benchmark for other researchers to develop their own approaches.

This type of quantitative measurement has not yet been performed on nerve rootlets, neither using standard nor fast MRI scans. Normally, these thin structures are not visible at all. But with this high-resolution dataset, machine learning models can be trained to detect and measure the nerve rootlets even if they are only faintly visible. The aim is to generate geometric models capable of generalizing across individuals.

Focus on the cervical region

For technical reasons, the cervical region is ideal for testing these tools. The acquisition technology requires special coils that need to be placed close to the region of interest. The cervical area is easier to access than the lumbar spine due to the shape of the body and the size of the coils. The cervical region therefore was an obvious starting point.

Acquiring data from the lower back is more difficult, but the measurement algorithms developed so far can also be applied to data from the lumbar region. Konukoglu’s group is currently testing this. “Also, it will be interesting for other research teams to adopt the existing tools and refine them”, he says.

Outlook

The overarching goal of the PHRT-funded project was thus to develop a faster MRI process capable of automatically identifying compressed nerve roots, thereby assisting physicians in their treatment decisions. The vision is clear: A patient with neck pain undergoes a 15-minutes MRI scan. The newly developed software analyzes the images automatically and provides quantitative information about the cervical spine. Based on these results, the physician can then decide whether to proceed with conservative treatments including physiotherapy and nerve root injections (a specific nerve root is identified as causing the pain), or if surgery is required. “Our goal is to empower physicians with precise information to guide treatment”, says Konukoglu.

Ender Konukoglu’s team is now training the models with patient data to work not only on the clean volunteer images but also on routine patient data, which are often noisier. Ultimately, the model has to perform well in clinical conditions.

Imaging and machine learning are the two pillars of Konukoglu’s work. His research operates at this intersection: advancing imaging technology and developing machine learning to solve specific clinical problems. While much remains to be done, these efforts bring the field one step closer to improving therapy for patients suffering from neck and back pain.

Prof. Ender Konukoglu

ETH Zurich