Success Story

Didier Trono Interview “Switzerlands Genetic Diversity is Unique”

Didier Trono

While other countries are pressing ahead with the Genome of Europe, Switzerland is still hesitating. A huge mistake, says Didier Trono from the Genome Center in Geneva

“I don’t want Swiss health data to be controlled by foreign tech companies in the US or China.”

PHRT: Where does Switzerland stand in the global landscape of genomic research?

Didier Trono: Switzerland has long been a leader in molecular genetics, but it has lagged behind in genomics—especially in population genetics and genomic medicine. While we have world-class research labs in human and molecular genetics, Switzerland did not take part in the Human Genome Project when it was launched on a global scale at the turn of the millennium.

Why did Switzerland choose not to participate?

It likely came down to a preference for waiting and leveraging the results once they became available. Large-scale international projects require substantial financial commitments, and Switzerland has traditionally struggled with securing large sums for singular research objectives.

What does that mean for present projects?

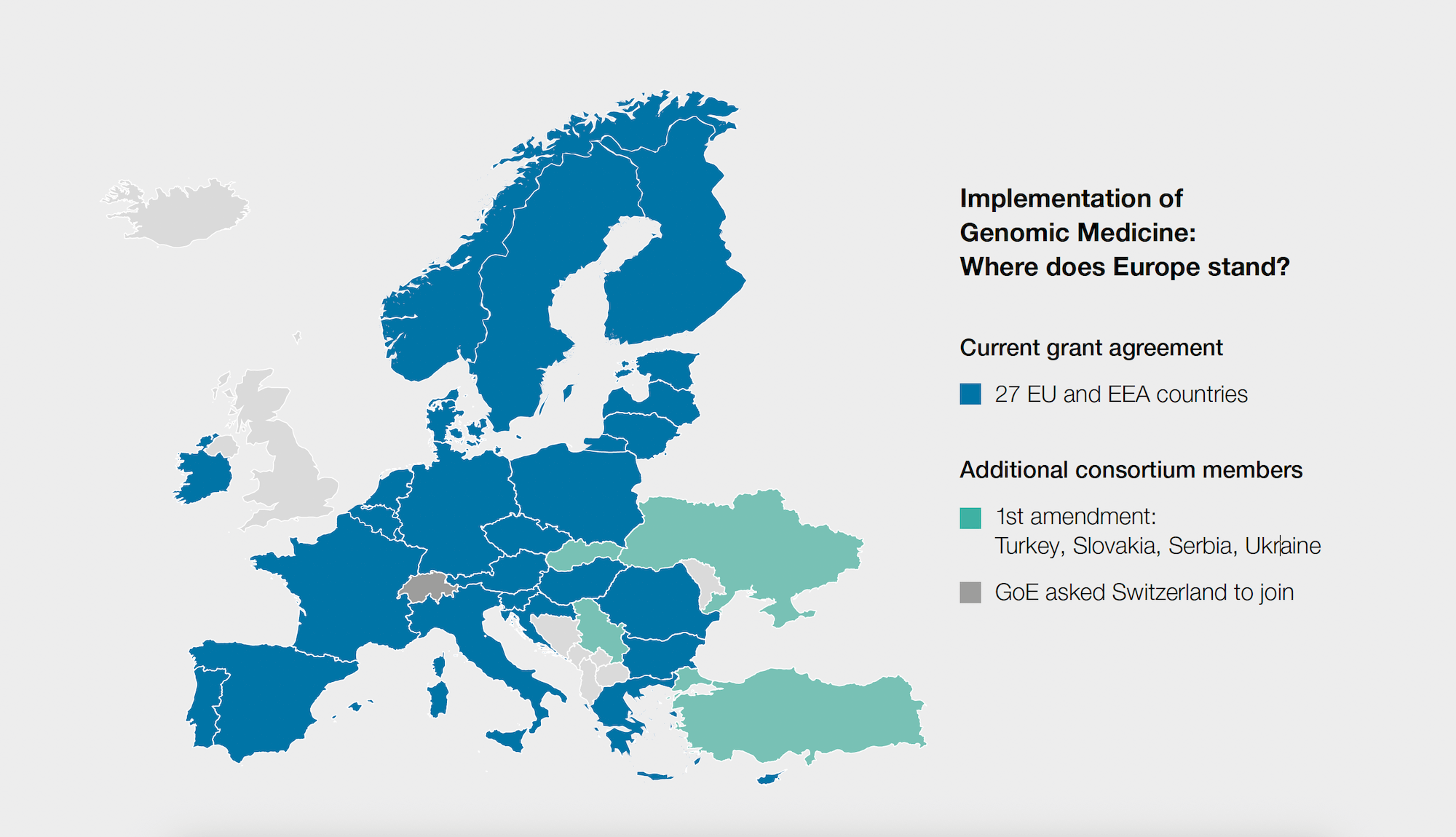

Other countries have invested heavily in sequencing their populations, while Switzerland is still hesitating. The US, Singapore, and EU nations are pushing forward, but Switzerland lacked the infrastructure to rapidly engage in such initiatives. Our small-scale, decentralized governance often leads to extended debates before decisive action is taken. Hundreds of thousands of genomes are being sequenced around the globe. This is generating a wealth of information, and technologies are being improved at a formidable speed. The Genome of Europe project will generate a reference dataset of >500,000 genomes of European residents, and will make this resource available to countries that have contributed their “fair share” of sequences. Thirty-one European countries so far are participating in this project, and Switzerland is not one of them.

But there is genome research being conducted in Switzerland.

Yes, but it’s fragmented. While some sequencing has been done as part of research projects, there has never been a coordinated national effort. It is only recently that initiatives such as SPHN and PHRT have pushed to set up a genomic research framework. The problem is, we entered the game quite late compared to our international counterparts.

What role did PHRT play in this?

Together with SPHN, PHRT took the lead in establishing a national genome sequencing project. Without this kind of initiative, Switzerland risked losing access to critical data. Initially, we were only observers in the European genome project, with no direct influence. It wasn’t until the “Genome of Switzerland” initiative was proposed that we started making real progress.

What is the Genome of Switzerland?

To be part of the European genome project, Switzerland needs to sequence around 15,000 genomes. It will allow Swiss-based researchers and healthcare providers not only to access the Genome of Europe dataset, but also to join a forum where precision medicine is discussed and shaped at a continental level. The first phase involved sequencing 1,000 genomes as proof of concept.

“Unfortunately, Switzerland still focuses more on treatment than on prevention.”

Were there ethical concerns from the public about sequencing?

Samples for the pilot phase came from the CHUV biobank and were processed according to a protocol approved by the cantonal ethics committee. We used an opt-out approach, whereby participants were informed and given the option to decline. In the end, less than 2% opted out, which shows that there’s strong public interest in genomic research and much less resistance than commonly thought. For the full-scale project, we will use new technologies allowing a more complete and in-depth sequencing of the genome. Earlier approaches, while highly efficient, did not yield clear insights into what many still call “the dark genome” which accounts for more than 50% of our DNA that is derived from virus-like genetic elements and is increasingly recognized as playing fundamental roles in human biology and disease. Some groups in Switzerland have developed world-leading expertise in this field.

How is the project funded?

Sequencing the first 1,000 samples was jointly funded by PHRT and SPHN. But now we need about 12 million Swiss francs to complete the full-scale project. We are looking for support from both private and public sources. In a joint response, the heads of the State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI) and of the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) turned down a request for support for the Genome of Switzerland project, citing the difficult federal budget situation and a lack of legal basis for financing this type of project. Thirty-one European countries are participating in the Genome of Europe project, with the EU covering only 20% of its costs. The UK was early to identify genomic science as a cornerstone of future health management and is investing heavily in this field, as are the US, Singapore, China and others. It is very worrisome that the Swiss government fails to identify genomic medicine as a strategic priority. Consequences could include second-rate medical care, or the management of our health by foreign companies that may not share our ethical values or may operate under the authority of governments with nationalistic priorities.

What will be the key benefits of this research?

Genetic factors play a role in nearly all human diseases, and, accordingly, genomics constitutes an essential pillar of precision medicine. A prerequisite to the practice of personalized health and precision medicine is to acquire a good knowledge of the genetic diversity present in the population and to apply frontline technologies within a legal framework that reflects the core ethical values of our society. In oncology, sequencing tumor genomes is already a standard approach for optimizing treatments. If Switzerland does not step up its efforts, it risks lagging behind in this critical field. Genomics also plays a major role in prevention. By identifying genetic risk factors early on, we can implement proactive health strategies. Take pharmacogenomics, for example, which helps determine which medications work best for an individual based on their genetic makeup. It is simply not acceptable that patients in a rich country such as Switzerland continue to receive ineffective or even harmful medication, just because genomic screening is not being utilized as it should be.

Is artificial intelligence being used in this research?

Absolutely. Machine learning is essential for analyzing the vast quantities of genomic data being generated. Many patterns in genetic data can only be detected through statistical modeling and AI-driven analysis. Medicine has always been somewhat empirical—treatments often work before we fully understand why. AI allows us to identify meaningful patterns and drive discoveries at an unprecedented pace. But even with AI, you need data to train your models and to gain a better understanding of the mechanisms. Without large-scale sequencing, there is no such data to feed the algorithms.

Why is it critical for Switzerland to be part of the European genome project?

First, it is the expertise. If we do not do our own sequencing, we remain dependent on others and cannot advance our own technology. Second, it is representation. Switzerland’s genetic diversity is unique, and excluding our population from these databases would be a missed opportunity. Lastly, it is autonomy. I don’t want Swiss health data to be controlled by foreign tech companies in the US or China. It is a matter of national sovereignty in one of the most sensitive aspects of life.

How long will it take to sequence the 15,000 genomes?

With proper funding, we could finish within a couple of years. We have the technology and expertise in place; we just need financial backing.

Do you think genomic awareness is increasing in Switzerland?

Yes, it is, but we definitely need more education in politics, in the training of physicians and also among the public. Preventive medicine ultimately saves costs and improves quality of life. Unfortunately, Switzerland still focuses more on treatment than on prevention. That mindset needs to change.

What’s your final takeaway?

Switzerland has the potential to become a global leader in the field of genomics, which is not only a pillar of modern healthcare but also acts as a catalyst for the growth of health-related companies. The people of Switzerland are ideally suited to take responsibility for their health if provided with all the necessary information. We have an educated population, top-tier research institutions, and the financial capacity to invest. The Genome of Switzerland project and the skills it will foster will empower our country to exercise full sovereignty over the generation and use of highly sensitive information to deliver the highest standard of healthcare to its people.

Didier Trono

About:

Born 1956 in Geneva, Switzerland

Dissertation in medicine, University of Geneva

Assistant professor at the Salk Institute, La Jolla, California

Professor at the University of Geneva

Professor at the EPFL

Research focus: virology, genetics and personalized medicine