Success Story

Interview: Microfluidic drug testing could improve cancer therapy

Interview

Microfluidic drug testing could improve cancer therapy

In this interview, EPFL researcher Christoph Merten describes an oncology platform developed by his team that can predict which cancer drugs are most likely to benefit individual patients. The aim is to move beyond “one-size-fits-all” standard care by testing a patient’s own tumor cells against many known therapies in parallel.

What is the overarching aim of your research?

The idea that there is one standard cancer therapy that works for every patient is outdated. We know that different cancer patients need different treatments. There was a lot of hope that genome sequencing would benefit patients. But in fact, this information is quite limited and in most real-world cohorts only a very small fraction of patients benefits directly from a genomics-guided therapy. So, our approach was to complement genetic data with functional data: We expose a patient’s tumor cells to drugs and combinations of drugs and then measure the cells’ response. So, our aim is to enable oncologists to find out which medication works best for a given patient.

What is the exact procedure?

Let’s say we have a cancer patient who is eligible for different treatments, but we don’t know which one works best. We collect a very tiny piece of tumor tissue from that patient, on the order of ten milligrams, and then we use microfluidics technology to build miniaturized screening platforms and run assays to find which drugs best kill the patients’ cancer cells. Because of this miniaturized model, we can test many more samples than what we would be able to do with conventional technology. This also makes it a lot more affordable.

What does a typical screening look like?

Microfluidics technology works with miniature droplets with less than a millionth of a liter, half a microliter of fluid. Each droplet represents an isolated micro-experiment containing patient cancer cells plus the drug. We use about 3000 individual assays to test drugs separately but also in combination. The combinatorial space is relatively large: drug A, drug B, drug A plus B, etc. Our goal is not to identify new cancer drugs, all the drugs that we test have been approved. We want to find which drug works best for which patient at a given stage of the disease.

How do you measure if a drug is successful inside those droplets?

We started out with reagents that generate a fluorescent signal if the drugs kill the cancer cells inside the droplet – so-called fluorescent apoptosis reporters. We would generate thousands of droplets including cancer cells and drugs, incubate them overnight and then measure the light signal the following day. A strong signal indicated that this patient reacts well to this specific drug or drug combination. So, when PHRT began, we had just arrived at the point where the light signal correlated with the efficacy of the drug.

What’s happened since?

Well, it turned out that the light signals did not tell us too much about the cell processes. So, during the PHRT project we switched to a transcriptomic readout: instead of measuring the light signal, we measure RNA sequences. The RNA tells us which pathways in the cells are turned on or off, allowing us to get a blueprint of the cell after exposure to the drugs. We did this for 420 different drug combinations. This approach is much more powerful because it allows us to assess which drugs work well and also because it improves cross-drug comparability. But, still, the method is quite slow and expensive. Thanks to a PHRT bonus grant we developed a high-content microscopy imaging on cancer cells. We’re hoping that in the future by doing very high-quality imaging we will get data sets that may replace the RNA-sequencing. That would be much faster and much cheaper. But we are not there yet.

Is your model being tested in the clinic?

We want to compare our measurements with the clinical outcome. To achieve this, we need robust clinical data. On one hand we collaborated with St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in the US, looking at a particular type of leukaemia in children called ALL. Using these patient samples, we saw first promising trends in terms of correlation between our microfluidic predictions, other assays carried out at St. Jude’s and the clinical outcome. We now have even more impressive results from a further collaboration with Freiburg University Hospital in Germany where we are focusing on advanced oesophageal cancer receiving neoadjuvant therapy. We could show that our assays align well with the clinical outcomes. The most responsive patients in the clinic were the ones who showed the strongest response in our microfluidic system. And the poorest responders showed no response in our assays.

How many patients were included?

About 30 patients, but we had some dropouts due to personal reasons. So far, we only tested oesophageal cancer patients in this collaboration, but we are thinking about using the assay in other cancer types such as colorectal cancer.

What needs to be done before this method can reach the clinic?

We are currently working on how to predict clinical outcomes just from sequencing. One way of doing this is to compare the sequencing data between clinical responders and non-responders. A particular gene may be expressed at a very high level after the drug treatment only in the responders. Then we could use the expression of this gene as a direct predictor of drug response. This is ongoing work. We don’t expect one universal model – biology differs too much between, say, leukaemia and oesophageal cancer – so we’re embracing disease-by-disease optimization.

You’ve set up a company. What does translation to practice look like?

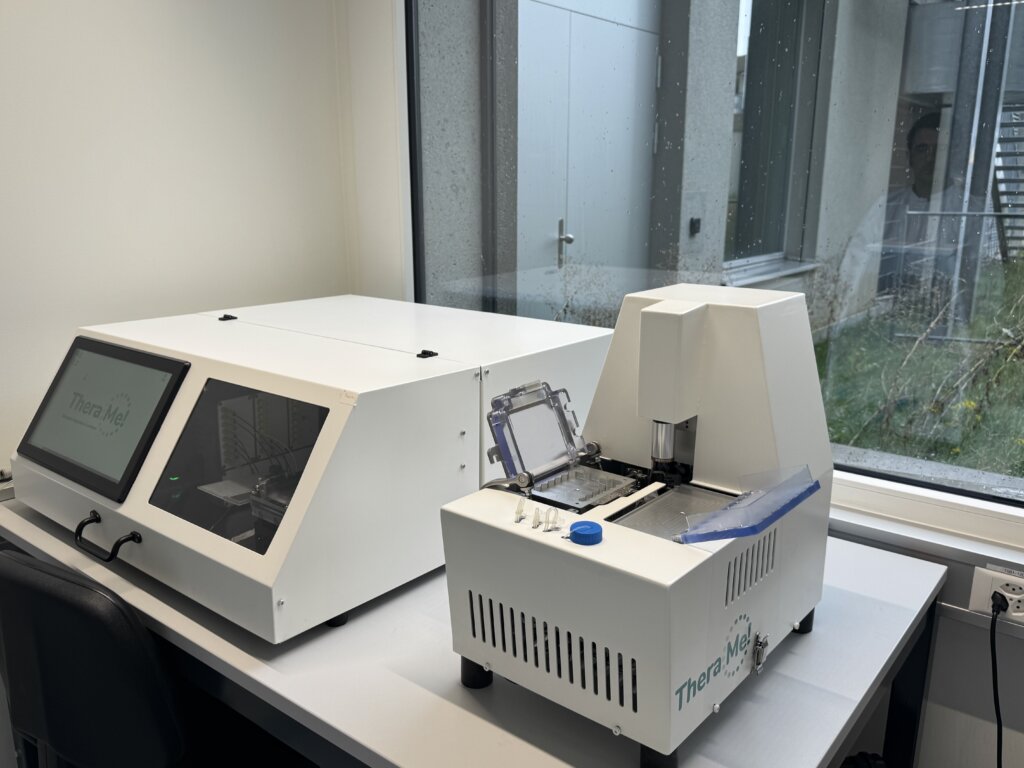

Yes, we founded TheraMe! AG in Lausanne in 2023. The academic prototype – lots of tubing and hand-loaded syringes, filled with highly toxic drugs – has by now become a closed, pressurized system with disposable reservoirs. We’re moving toward a plug-and-play instrument with pre-loaded drug cartridges and automated fluidics so that it can be run safely and reproducibly. For that, we are collaborating with engineering partners like CSEM (Centre suisse d’électronique et de microtechnique) and using dedicated innovation funding to industrialize such as Innosuisse.

What role did PHRT play in all of this?

PHRT helped us turn a cool lab demo into a platform with a real path to everyday precision oncology. PHRT enabled us to launch a start-up and bring this promising technology closer to the clinic. Before you can bring a diagnostic device into the clinic, it needs to be CE-certified. An industrial device is on the way. If all goes well, and the performance study for the CE approval is successful, we might start first routine use for a specific indication within two to five years, with Switzerland likely being the initial market.

Interview: Luzia Jäger and Theres Lüthi

Christoph Merten

EPFL Researcher